Jim Stinson Recalls Hunting for Autographs, Memories in Castro’s Cuba

Contents

It was 1998. As I looked out of the jet’s window and watched the lights of night-time Havana draw closer I knew that this trip would be different. Since the Kennedy administration most Americans had been barred from visiting Cuba, our Caribbean cousin located just 90 miles south of Key West, FL. I had family on the island and my request for a legal visa had been granted.

From the mountains and tobacco fields of Pinar Del Rio to the west to the sun drenched beaches of Santiago province to the east, the island is an amazing 1,000 miles long. The capital city of Havana rests on the northwestern coast. As a long time sports fan, Cuba had always fascinated me.

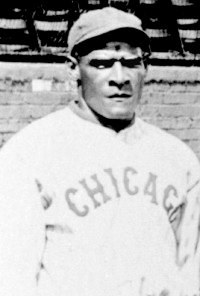

The country’s own obsession with sports has produced some of the greatest athletes in history. In the 1920s and 30s many of the brightest stars in the Negro Leagues were Cuban. There was no color line in Cuba so players too “dark” to play in the major leagues would share the field with white players during the winter months. Virtually the entire Negro Leagues would play summer ball in the States and winter ball in Cuba. Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Oscar Charleston, John Henry Lloyd and others all played there. Native born Cubans like Cristobal Torriente and Jose Mendez excelled there.

Jose Mendez

During a series with a U.S. all-star team that included Babe Ruth, Torriente outhit Ruth as the Cubans beat the Americans.

John McGraw, who traveled extensively in Cuba, said Mendez was Walter Johnson and Grover Alexander rolled into one.

Probably the most revered of all Cuban players, Martin Dihigo, could play anywhere on the diamond. Hall of Famers Monte Irvin and Johnny Mize, who both saw him play, called Dihigo the best all-around player– white or black– they had ever seen.

Professional boxing also flourished in Cuba, with names like Kid Chocolate, Kid Gavilan, Sugar Ramos, Jose Napoles and Teofilo Stevenson (more about him later).

Land Lost in Time

I arrived on the island not knowing what to expect. The contradictory facts and fables that await a tourist in Cuba are as diverse as the island itself. My previous travels had taken me from Thailand, where I worked as a professional boxing judge, to Rome, where I visited former middleweight champion Nino Benvenuti.

Cuba was– and is–unlike any place I have ever been. When asked to explain, I can only say it’s like traveling in a time capsule back to 1959. Time, in many ways, has stood still since then.

Havana, Cuba

My plane touched down and I exited into the stifling heat of the airport terminal. I was in Cuba!

A waiting bus shuttled me and the other passengers to the terminal and customs. The ten-minute ride was bumpy, uncomfortable and oppressively hot. The airport itself is an ultra-modern facility, completed with the help of the Canadian government. For some reason which I can’t quite understand, passengers leaving the island depart through the new terminal which is air conditioned and spotlessly clean. Arriving passengers, however, are brought into what used to be the old airport, which is not air conditioned.

The checkpoints at customs went well. I was met by various officers dressed in green military fatigues. They asked if it was my first trip to Cuba, where I would be staying and the purpose of my visit. After a brief conversation in Spanish they eyed my computer suspiciously and said “journalist?” I told them no and after an uncomfortable silence was told to “have a good time.”

My trip would produce astonishing images– and a near death experience at the hands of a drunken former Olympic champion.

The Mission

There were several things I wanted to accomplish on this trip. I wanted to meet one of the island’s foremost baseball historians regarding the player they call “El Inmortal.” Dihigo is the only baseball player in history to be enshrined in the American, Cuban, Mexican, Dominican and Venezuelan Halls of Fame. I wanted to visit the town where Dihigo lived out his life after baseball.

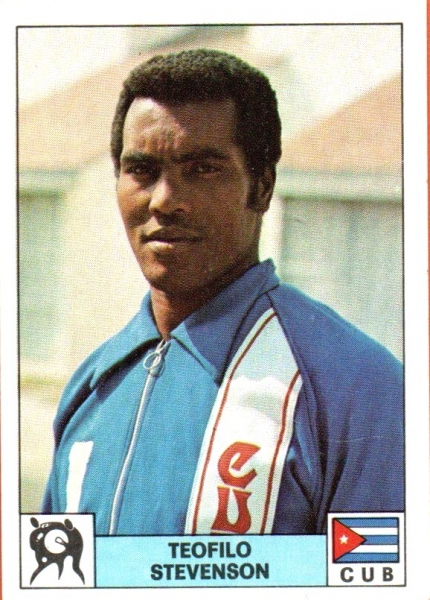

I wanted to meet the greatest Olympic boxer of all time, three-time gold medal winner Teofilo Stevenson. Most collectors had never even seen Stevenson’s autograph and I was told that although he would not accept money that he would consider signing a specific number of items in exchange for “gifts” for his family that included name brand athletic gear that was nearly impossible to find on the island.

I also wanted to locate the family of the legendary Cuban boxing champion Kid Chocolate, in hopes of securing some signatures.

A “Rum In” with an Olympic Boxing Champ

After the revolution in 1959, Fidel Castro embraced communism and created an alliance with Russia. In the years that followed, this would create a lopsided and confusing social and economic system. Fewer than 1 out of 150 Cubans owns a car, 1 in 75 owns a telephones and a doctor who typically drives to work on a bicycle or walks, earned the equivalent of $40 per month. The average Cuban earns much less. Despite this, Cuba is one of the safest and most crime free countries I have ever visited. The penalties for even petty crime, especially against tourists, are severe. A simple crime like stealing a watch would be met with a two-year prison sentence. Violent crimes are dealt with swiftly and severely and, for the most part, are extremely rare.

Teofilo Stevenson was the star of Cuba’s amateur boxing team for over 15 years and is generally regarded as one of the greatest heavyweights of all time. He won gold medals in the 1972, 1976 and 1980 Olympics. To further underscore his amazing accomplishments, he also won gold medals in the World Amateur Championships in 1974 and 1978. What is not reflected in the cold hard facts was his sheer dominance and awesome knockout power. Few of his opponents ever came close to beating him.

At the height of his career, American promoters offered him a mega-million dollar deal to fight Muhammad Ali but it never happened, leaving boxing fans to forever ponder the question of what might have been.

At the time of my visit, Stevenson lived in an unpretentious home in Havana with his fourth wife, a criminal attorney who was 20 years younger than the former Olympian, and a son who was then five years old. Teofilo or “Teo” as his friends called him, was heavily involved with Cuba’s athletic programs. He stood 6’5″ but actually looked taller and weighed a fit 238 pounds. He was muscular with arms that seem too long for his body. His hands were massive. He spoke in a deep baritone that commands and is given respect.

Stevenson is a tough autograph to find. He has been barred from entering the United States after assaulting a Miami airport employee. Weeks prior to my arrival, Cuban police had stopped his car. It was dark and the officer in charge made the mistake of not immediately recognizing Stevenson and asked for identification. Stevenson reached out one of his huge hands and ripped the police officer’s badge along with his shirt off of his body. A scuffle ensued, back up was called and when the arriving army of police recognized him, he was released.

One of his neighbors had arranged a meeting and I was to visit his house on my second day in Havana. Stevenson likes to drink rum and easily consumes a bottle or more a day. For that reason our mutual friend informed me that it was best to arrive early in the day.

At close to 10 AM we entered the gate to his home, which was already full of visitors who eyed us suspiciously. Stevenson emerged from the kitchen and greeted us. He had a way of standing back erect and not moving his head to look at you but instead just moving his eyes, making this 5’10” writer feel a bit like Eddie Gaedel.

Author Jim Stinson and Teofilo Stevenson in 1998.

Although he spoke a little English, we conversed in Spanish or at least I conversed. Stevenson just grunted. My friend guessed he was already on his second bottle. I presented him with the Nikes and gifts for his family that I had brought and he agreed to sign the 300 or so 8×10’s I had brought along. After signing about 50 photos he stopped abruptly and told me he was “tired” of signing and that I should leave the rest of the photos and stop by to pick them up later. He got up and walked away, absorbed in a conversation in another room.

Baffled, I decided it was not a good idea to leave the unsigned photos as I might never see them again or worse, someone in the house would take on the uncompleted task and just sign his name for him, so we packed up and left.

When we returned about two hours later there was a strange silence in the house. I had brought back the photos which were tucked under my arm. Stevenson was in the back part of the house by the pool area. Fear hung in the air like a fog. When he saw me he stood straight up, his eyes as red as tail lights, “YOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOUUUUU!!!!” his voice boomed. I was to learn later that after we had left, Stevenson had begun to look for the photos he’d told me to leave. Being unable to find them, he accused everyone in the house of having stolen them. His tirade had continued unabated the two hours we had been gone. Now aware of the culprit, he was furious.

I was in the unenviable position of standing on the third step down from the patio deck while he stood on the top step staring down at me. This made the already tall fighter seem like a three story building. I noticed he was balancing himself on the balls of his feet. It was then I realized he was going to hit me. I wondered if I would actually see the punch coming. I stammered that I had misunderstood him and blamed the problem on my Spanish. “SO SPEAK @#%$& ENGLISH!!!!,” he shouted.

I looked to the neighbor that had accompanied me for assistance and saw that he was slowly moving backwards towards the exit. It was then that I thought of my plan of action should I actually get a chance to see the punch coming. Maybe I should try and fight back I thought, No that would only make him more angry. Maybe I should just run. No, there were too many witnesses and I could never live that down. I finally decided the most intelligent plan of action would be to just take the punch fall down very quickly being careful not to move and be prepared to lay there all day and night if necessary until he went away.

I figured I had time for maybe one question and at that point asked what was probably the most ridiculous question of my life.

“So does this mean you’re not going to sign the rest of the photos?”

He looked at me, stunned by the audacity of the question. One of his guests suggested I come back tomorrow when he was in a better mood. That was the exit I had been praying for.

I returned early the next morning and as I had expected he remembered little or nothing of the previous day’s events. He was a different man. Pleasant and smiling, he showed us around his house even stopping to relive some of the Olympic moments that had made him famous and proudly displayed photos picturing himself and Fidel Castro. He signed the rest of the photos, finishing in less than an hour. He then insisted I join him with a glass of rum which he poured for me in a large glass tumbler filled to the top—straight, no chaser.

Remnants of a Great Boxer’s Life

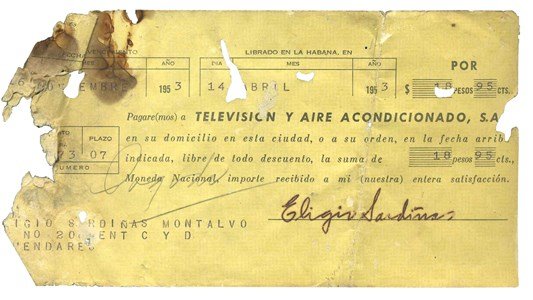

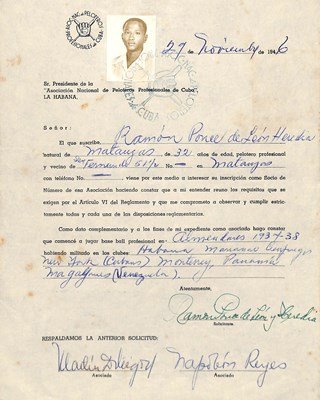

The following day I set out in search of the family of Kid Chocolate, the Hall of Fame boxer whose real name was Eligio Sardinas. After a brilliant amateur career in Cuba, in which he was rumored to have fought over 900 bouts with no defeats, the boxing world took notice and launched his professional career which would prove to be sensational. He would become one of the most dominant fighters of the 1930s, winning both the featherweight and super featherweight world championship. He fought in every famous boxing venue in the United States including over ten visits to Madison Square Garden.

After retiring in 1938, he returned to Cuba to live out the rest of his life in the house he had bought for his mother with his ring earnings. He would eventually die in that house at 78 years old in 1988.

For the most part, his boxing prowess and accomplishments have largely been forgotten. He is still considered by many to have been one of the greatest featherweights in history.

I knew the general area where he had lived and was told his family still resided there. After several inquiries I found it and knocked on the door. I was met with a small elderly man, very thin who greeted me at the door. It was Kid Chocolate’s son! When I asked him if I was in the right place, he smiled and pointed to a glass engraving above the door with the initials “E.S.” This was indeed the home of Eligio Sardinas.

He invited me in, curious as to why I would be interested in his late father who had by then become largely forgotten, even in his native country. Located outside of downtown Havana, the home was large and it was easy to see that at one time it would have been one of the most impressive in the area but like almost every structure in Cuba over the years, it had entered into disrepair.

When I explained to him what I was there for, he was elated and family members began emerging from every room. Children, grandchildren, cousins… I could not keep track of them all.

Newspaper article from 1998 about Jim Stinson’s visit to the family of Eligio Sardinas (Kid Chocolate) in Cuba.

After making our introductions he led me to a room of the house that was neatly kept. Several pairs of shoes sat near the door to the bedroom, he opened the closet to reveal his father’s clothes, all hung in the closet it was as if his father had left for a walk and would be returning any minute.

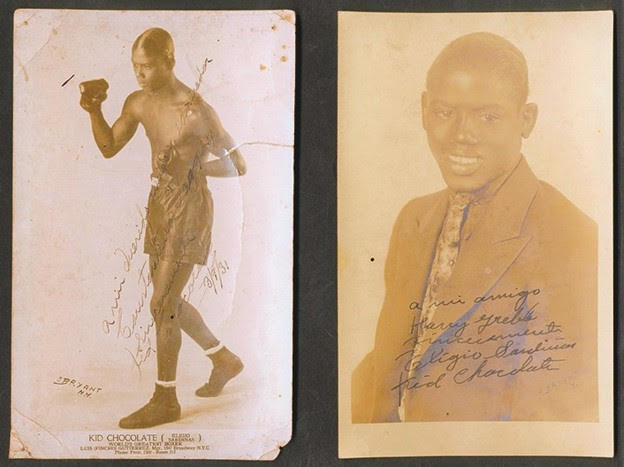

I explained to him that the autograph of his father was elusive. At that time, I had seen only a few ever offered for sale. The scarcity was mostly due to the relatively short time he spent in the States and the fact that once back in Cuba, he rarely if ever answered mail requests for his autograph.

“Kid Chocolate” autographed items, including one personalized to fellow boxer inscribed to boxer Harry Grebb. Photos from Lelands.com.

His son told me that after his father had died, officials from the Cuban government came to the house and had taken his various awards, belts and other memorabilia to be displayed in a “museum” which, sadly, not even his family could locate. Even worse, he told me of another visitor he had years earlier who came in search of anything signed by his late father. He was offered $400 for a signed passport. The mysterious stranger took the passport with a promise “to be right back” he never returned.

However, all was not lost his son pointed to three large burlap sacks that sat in the corner of the room that must have weighed over 100 pounds combined. These, I was told, were his father’s personal effects. We emptied the first sack on his living room floor it was full of fan mail his father had received, most dating to the 1950s and 60s. I was surprised at how many of the names of the collectors who wrote those “through the mail requests” were familiar to me.

Half of the paper in the sack had turned to dust and I was even more startled at the variety of insects that began running across the floor. An entomologist would have been ecstatic. I was looking forward to my next shower.

Things began to get interesting when we opened the second and third sacks, along with the dusty paper and more diverse varieties of insect life, we found letters his father had written, photos he had signed and even some personal checks. After what seemed like hours I was able to salvage about 15 to 20 Eligio Sardinas signed items. I was happy and his son was happier when I made him an offer, his knees actually buckled as he moved a few steps backwards. “Today?” was the only word I remember him saying. In his eyes I had turned from “Curious Gringo” to “Santa Claus.” I counted out the money, we all posed for pictures and yes, out came a bottle of Cuban rum.

Unraveling the Life of a Baseball Legend

My next adventure would be the search for the legacy of Martin Dihigo. That part of the trip would prove even more bizarre.

In Cuba signs of the communist philosophy are pervasive. Images of Che Guevara, the Argentine revolutionary who took up arms with Castro in the revolution of 1959, are everywhere. “Seremos como el Che” (We will be like Che) is spoken by every school child every morning in much the same way our children recite “The Pledge of Allegiance.”

Instead of advertising, billboards in Cuba boast political propaganda. “Patria o Muerte -Venceremos” (Patriotism or death -Victorious), “Te Sere Fiel” (I am loyal), “Aqui no se Rinde Nadia” (Here we have never lost).

Near the Hotel National, a downtown Havana landmark where virtually every celebrity from Frank Sinatra to the Brooklyn Dodgers used to stay when Havana was the playground of the Caribbean, stood a sign picturing Uncle Sam looking across the bay in the direction of the United States. It reads “Abajo Los Imperialistas Yanquis” (Down with Imperialist Yankees). In reality, the 60-plus year embargo imposed by the United States had done more to help Fidel Castro than to hurt him: to blame the economic hardships and sacrifices endured daily by the Cuban people on the United States. Four to six hour televised rants against the “Imperialistas” were the norm but in a country with only two TV channels, the average Cuban was furious when their favorite TV shows were pre-empted by “the bearded one.”

After my near pummeling at the hands of boxer Teofilo Stevenson the day before, I was eager to see some of the sights and to meet the man that is considered the island’s foremost historian on Cuban baseball. He lives in a small modest house on the outskirts of Havana with his wife and son. I had hoped to track down two impossible autographs, those of the greatest Cuban home run hitter in history, Torriente, who died in 1938, and Mendez, the island’s greatest pitcher, who had passed away in 1928. But foremost in my mind was Dihigo, whose name is most synonymous with Cuba. Facts surrounding Dihigo’s life were sketchy and I hoped with the help of the new Cuban friend I was about to meet, to set the record straight.

He had prepared for my arrival by carefully laying out his collection of Cuban baseball cards. Knowing nothing about cards I was nevertheless impressed. Most dated to the 1920s and were in immaculate condition. Some were complete sets and some, he pointed out to me, had never even been cataloged in American price guides. Impressive, yes. But I was there to talk about autographs.

He smiled and disappeared into a back room, emerging with a box he was careful to tell me was “not for sale.” He also warned me of something I had long suspected that almost all of the autographs of Martin Dihigo that come out of Cuba are forgeries.

“You would be surprised at how many Americans come here looking for Dihigo’s autograph,” he told me. Cubans have gotten very good at replicating the Hall of Famer’s signature and some of the worst culprits lived four hours away in Las Cruces, the small town where his family still lived. Most of the signed items I have seen over the years were Christmas cards, signed books and letters. These, I was told, were manufactured to supply the demand. Some rumors indicated there may have been involvement from Dihigo’s descendants.

The first Dihigo item he showed me took my breath away. It was his personal diary. Written in his own hand in Spanish, it began with a brief personal description of himself. This was especially interesting in that various historical sources have listed conflicting dates and falsehoods about his life. Here, in his own hand, he sets the record straight.

“Martin Dihigo Llanos was born in the city of Matanzas on May 25th, 1906,” he writes. “The street is called good trip (Buen Viaje) and it was at number 40 where I saw the light of life for the first time. Through the years I have been a sportsman. Why for someone else you could be born in Europe where a man is born a man, with equal rights in the different things of life….Poor Cuba!”

The other pages offered other insights into his feelings regarding friends and teammates but most interesting were the entries detailing numbers and amounts owed. Martin Dihigo, it appears, was running numbers and kept a record of his illegal lottery dealings as well as what would be called today loan sharking.

My Cuban acquaintance also produced documents which proved that Dihigo was never involved as “minister of sports” or in any official capacity with the government. He was involved in baseball his entire life as a player, coach and manager, and in the 1950s became involved with a players association that was very similar to our own baseball union.

Shortly after the Cuban revolution, Dihigo suffered a series of strokes and returned to his home town of Las Cruces where his health grew worse. His health kept him from signing autographs for nearly ten years before his death in 1971. In the 1960s, rumors had circulated around the island that he had died or had even been executed. To prove the rumors wrong, a seriously ill Dihigo agreed to a radio interview that was broadcast across the island.

Six years after his death, he was among the first group of former Negro League players inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY, but in a land where the fight for daily survival is paramount, the memories of long deceased national heroes are easily forgotten.

Cemetery in Las Cruces Cuba; Martin Dihigo’s final resting place/Photo by Jim Stinson.

I wanted to visit his final resting place and made the four hour drive to a small cemetery located outside of Las Cruces. Horse drawn buggies outnumbered cars in this land that time had forgotten, but finally I found it. A group of Cubans were excavating graves as is the practice there. After three years in the ground, the deceased are dug up and their remains labeled and stacked floor ceiling in the various mausoleums that dot the cemetery.

I was directed to a building where the remains of Martin Dihigo were housed. Looking for his name on the ossuary, I found none. One of the cemetery workers began unstacking metal boxes until he located one with Dihigo’s name on it. He asked if I wanted to see him and before I could answer opened the box containing his remains.

he next day I returned to Havana. On my last evening I stood on a balcony leaning against a cast iron railing overlooking the narrow streets of old Havana. I sipped my Cuban rum and exhaled the smoke from my Monticristo. I wondered when I would return. I had come to look at the island’s past and my experiences there were not something I would soon forget.

I watched the smoke from my cigar rise overhead and disappear above me as the warm breezes blew softly down the ancient streets of old Havana.

POSTSCRIPT

Teofilo Stevenson died in 2012 age 60 of a massive heart attack. Fidel Castro would eventually pass away in 2016 after a prolonged and much publicized illness. I returned to the island and went to visit the historian who had been so helpful with information regarding Cuban baseball and Martin Dihigo. After several trips around the block I could not find his house. Finally a building appeared that looked nothing like the house I had visited on my previous trip. It had been completely remodeled and had a fresh coat of paint. He was pleased to see me and explained that an American collector had visited him and bought the majority of his Cuban baseball card collection.

I decided to take one last stab at information regarding Mendez and Torriente, who had by now been inducted into the Baseball Hall Of Fame and probably the rarest autographs of any of its members.

Cristobal Torriente

This time I had addresses where they had lived. After knocking on many doors mostly in old Havana, I learned the current residents had never heard of them. Quite by luck, I located the closest living relative of Cristobal Torriente, who was now in her 80s. Her grandmother was Torriente’s only sister. She told me she had grown up in the house that Torriente had bought for himself and his mother shortly before his death. She said the house was made of wood and she remembered as a young girl it was falling apart. Prior to moving, she and her mother had made a large bonfire in the yard and told me she remained certain that many of Torriente’s momentos were in that bonfire.

She told me that her grandmother had told her that the last wish of Torriente was to return to Cuba as he lay dying in a New York hospital. After his death there in 1938 he was buried in a pauper’s grave in New Jersey. In the 1940s, someone arranged to have his remains returned to Cuba. Like Dihigo, they were in a container in a vault in Cristobal Colon cemetery along with those of about 20 other Cuban baseball players. It was a “monument” built in the 1940s by other Cuban players who were living at the time. I visited that too. In the dark, dank area were small boxes, laying side by side, of the players whose names are etched into the front of the memorial. The room is infested with rats and empty rum and whiskey bottles. I was told later, but could not confirm, that they performed DNA testing on the remains believed to be Torriente’s and were conclusive that one of the boxes were indeed his. I was told that a private plot was purchased and his remains are now respectfully underground.

My search for Jose Mendez proved fruitless. I was, however, able to locate the hospital where he drew his last breath in 1928 which is now an apartment building and the church around the corner where his funeral was held. He, too, is in the same cemetery as Torriente but was long ago buried in his own plot. In an odd twist, I was able to uncover that Mendez married an American woman who, according to census records, was still alive and living in Kansas City in the 1970s, working as a cleaning woman.

I still find in fascinating that many of the most ardent sports fans in Cuba have never HEARD of Torriente or Mendez or Kid Chocolate or Martin Dihigo or any of the hundreds of Cuban legends of sport that lived before the revolution. The current regime has managed to eliminate most of its history prior to that time.. It will remain up to people like me and those that come after to put the pieces of the puzzle that is Cuba back together again.

In addition to telling some great stories, long-time autograph dealer Jim Stinson offers vintage sports autographs for sale via his email list. You can follow him on Facebook too.