The ABA Story, Part II – Rookie Cards of Eight ABA-Only Greats

Several weeks back, we strolled down memory lane, reliving the delightful – and delightfully weird – heyday of the ABA. Anyone truly familiar with basketball history will recognize a common thread among those highlighted in that piece. Not only were these among the most accomplished of ABA alumni, but NBA success also lay in their future. Julius Erving, Rick Barry, Artis Gilmore and Dan Issel reached their respective peaks in the ABA, but all also enjoyed significant post-merger stardom in the NBA.

For George Gervin and Moses Malone, time in the ABA was fleeting, as the renegade league was on its last legs by the time they arrived. They certainly rank among the league’s most notable alumni, but the greatness that defines their careers came in the NBA.

There is, of course, another breed of ABA star, for whom the music stopped when the red, white and blue balls were put away – if not, sadly, before. We’ve already discussed one such player, Marvin Barnes, whom I’ve described as “one of the most ABA players ever”, a renegade, in a renegade league. Had I known this follow-up was coming, Marvin would have wound up here (in all honesty, I’m glad we got to him first).

Barnes’ arc is by no means uncommon. There is a crop of era-defining players and characters whose exploits – through some combination of injury, indiscipline and, well, other stuff – are confined to those wild nine years. Theirs are stories that would be forever be lost history, if not for the accounts of those fortunate enough to see them firsthand (a standard reminder to read, or re-read, Terry Pluto’s Loose Balls), and those of us who didn’t, but share a desire to keep those memories – and those of the 1971 Topps basketball set – alive.

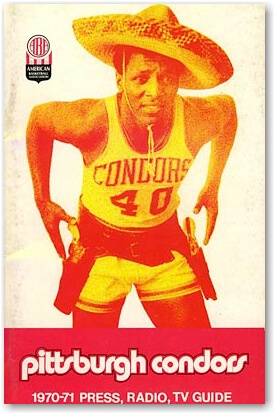

John Brisker (Pittsburgh Pipers/Condors) – 1971 Topps #180

We’re coming out hot here. Where to even begin with Brisker?

Not a lot is known about Brisker’s youth. What’s confirmed is that he was extraordinarily tough. He was, after all, forged on the playgrounds of Detroit. After high school, he received a scholarship to play college ball for Toledo. After flunking out during his senior year, in 1969, he jumped to the ABA’s Pittsburgh Pipers (later the Condors), joining friend and fellow Detroit native Spencer Haywood, whom Brisker had known since youth.

That Brisker spent just three seasons in the ABA just seems off. On the one hand, it’s wild that a character who so embodied the ethos of a league did his damage in so short a time. On the other hand, it’s a wonder he lasted as long as he did.

His first season, 1969-70, ended with him being named to the ABA’s All-Rookie First Team. Over the next two seasons, he averaged an awesome 29.2 points and 9.5 rebounds per game, and was named an All-Star twice.

After the 1971-72 season, in the midst of a contract dispute, Brisker jumped to the NBA, again joining Haywood, this time with the Seattle Supersonics. In three NBA seasons (really just one, and 56 games over two others), he averaged just under 12 points and four rebounds, and thoroughly infuriated Celtics legend Bill Russell, who’d been hired as head coach and team president before the ‘73-‘74 season. After being cut from the Sonics, Brisker spent a single season with the Cherry Hill Rookies of the Eastern Basketball Association (later the CBA), after which his pro basketball career came to an end. In 331 ABA and NBA games, Brisker averaged 20.7 points and 6.5 rebounds per game.

Those are the raw facts. This, however, is a man for whom mere “facts” are insufficient. With Brisker, it’s about the legend.

There was, by ALL accounts, an anger with which he played, that, very generously, was something of a double-edge sword. Brisker was legendarily volatile and violent. In the words of former teammate Charlie Williams: “say something wrong to the guy and you had this feeling he would reach into his bag, take out a gun and shoot you.” An enforcer of the highest order, Brisker was a powder keg seemingly always seeking out a matchbook.

There are stories of Brisker running onto the court during practice, waving a gun.

In 1971, he was ejected two minutes into a game for an elbow on the Rockets’ Art Becker. He returned to the court three times go after Becker, only relenting under threat of arrest.

That same year, he was arrested outside of Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium during a World Series game, after an altercation with the police, which sent two officers to the hospital.

The Utah Stars hosted a “John Brisker Intimidation Night”, during which they had a crew of professional boxers on their bench.

Former ABA and Sonics coach Tom Nissalke put a $500 bounty on Brisker before a game. When playing for Nissalke in NBA, Brisker joked that this was “a pretty good move”.

In 1973, less than a week into his second NBA training camp, Brisker clashed with teammate Joby Wright. Wright left the gym in an ambulance, with a shattered jaw and four fewer teeth.

Here’s where it gets weird.

According to Haywood, by the late 1970s, Brisker was in some “dark, shady places”. Haywood believed he’d seen a picture of Brisker with Ugandan dictator Idi Amin. It’s since been reported that, in March 1978, Brisker travelled to Uganda to launch an “import-export business”, with the last confirmed communication from him coming on April 11, 1978. What happened afterward remains a mystery, though folks are more than willing to float theories.

Haywood said he heard that Brisker was “caught up in that coup in Uganda.” Tom Burleson, another ex-teammate, claimed that Brisker, fighting as a mercenary, was captured and killed by Idi Amin’s men. According to Slick Watts, he was shot in an argument with Ugandan royalty. Brisker’s own brother claimed that he was not even in Uganda, but in Nigeria, where he owned land.

For the purpose of settling his estate, Brisker was officially declared dead in May 1985. However, the U.S. State Department, who couldn’t confirm that Brisker had travelled to Africa, stated that “essentially, we don’t consider him dead”. Meanwhile, in 2017, the Seattle office of the FBI (why not, right?) “could not conclusively say if the FBI was involved or not.”

That’s probably too ABA. Even for the ABA!

Of course, you’d never know it from the smile on Brisker’s face on his 1971-72 Topps rookie card, which can be found in high grades for between $45 (PSA 8; pop: 79) and about $150 (PSA 9; pop: 36). A true, of-an-era relic.

Roger Brown (Indiana Pacers) – 1971 Topps #225

For reasons far less problematic, Roger Brown will forever be “one of the most ABA players ever”. Unlike Brisker and Barnes, the issues that hindered Brown ’s career and kept him from the NBA were not of his own creation.

Like another New York native from the era, Connie Hawkins, Brown, an ultra-talented 6’5″ wing, starred in high school in Brooklyn in the late-1950s. In 1960, he signed to play for the University of Dayton. Sadly, like Hawkins, Brown was banned from both the NCAA and the NBA because, while in high school, he’d been introduced to gambler Jack Molinas, who was involved in illegal point shaving. Like Hawkins, Brown was never accused of anything beyond meeting Molinas, but still spent over half a decade in the wilderness before finding a path to the pros.

In 1967, Brown, then living in Dayton and working for General Motors, signed with the Indiana Pacers, as the organization’s first-ever player. During a stellar eight-year ABA career with the Pacers, Memphis Sounds, and Utah Stars, he averaged over 17 points and six rebounds, and nearly four assists per game. Deadly both in isolation and on the perimeter, he was named an All-Star four times, All-ABA First Team once, All-ABA Second Team twice, and helped the Pacers to three ABA championships. Brown was selected to the ABA’s All-Time Team (released in 1997) and, in 2013, was one of five inductees into the Hall of Fame by the Hall’s ABA Committee.

Brown’s defining moment came in 1970, when he scored 53, 39 and 45 points in last three games of the championship series, earning playoff MVP. Brown’s popularity in Indianapolis at this point was such that, in 1971 – while still an active player – he won an at-large election for a seat on the City Council.

Brown, who passed away in 1996 after a battle with cancer, is one of just four players (along with Reggie Miller, George McGinnis and Mel Daniels) to have his jersey retired by the Pacers.

As a result, his delightfully-hued rookie card, also from the 1971 Topps set, is a fairly hot commodity, with PSA 8 versions still topping $150, and PSA 9s, when available (there are only 26), topping $500.

Mel Daniels (Indiana Pacers) – 1971 Topps #195

As great as Roger Brown – and later Reggie Miller – were, the greatest player in the history of the Indiana Pacers is Mel Daniels. Daniels spent his first professional season with the Minnesota Muskies (whom he’d chosen after also being selected ninth in the 1967 NBA draft), with whom he averaged 22 points, a league-best 15.6 rebounds, was named both an All-Star (his first of seven straight selections) and the ABA’s Rookie of the Year.

After his rookie season, with the Muskies in financial distress and in the process of relocating to Miami, Daniels acquired by the Pacers for a reported $75,000. What a steal.

In his first season with the Pacers, 1968-69, Daniels averaged 24 points and a (again) league-leading 16.5 rebounds, and was named league MVP. He replicated the feat in 1970-71, with averages of 21 and 18 rebounds. In his first six seasons as a pro, Daniel averaged 20.5 points and 16.6 rebounds per game, and was named All-ABA First Team four times. The worst of those seasons, 1974-75, still saw Daniels average 18.5 points and 15.4 rebounds per game. All the while, the Pacers were building the ABA’s lone dynasty, winning three titles (1970, 1972, 1973) in a four-season span.

Daniels is the fourth leading scorer in ABA history, and the league’s all-time leader in total rebounds, offensive rebounds, defensive rebounds and rebounds per game. Perhaps most importantly, Daniels is credited by some with saving the Pacer franchise, which, in the absence of his (and Brown’s) star power, might well have folded prior to the merger.

For his efforts, Daniels was selected, unanimously, to 1997’s ABA All-Time Team, inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2012, and had his #34 retired by the Pacers. After spending the 1975-76 season in Italy, Daniels did sign for a brief stint with for the New York Nets after the merger, but 628 of his 639 career games were in the ABA.

Like Brown and Brisker, Daniels made his cardboard debut in the 1971 Topps set. Ungraded examples of his rookie card are relatively inexpensive, while PSA 7s (pop: 79) sometimes top $100, PSA 8s hit $200 (pop: 91), and 9s (pop: 32) eclipsing $700.

Bob Netolicky (Indiana Pacers) – 1971 Topps #183

It would have been easy to dismiss Bob Netolicky, the son of a surgeon and “the Joe Namath of the ABA” as a flighty rich kid who coasted through life without a care. And, sure, “Neto” was an exotic pet enthusiast (he reportedly had, at least, a lion and an ocelot), a nightclub owner and an extremely willing recipient of attention from the ladies…

The thing is, this was all more feature than bug. Netolicky was a beloved teammate, something of a spiritual leader, and coach Slick Leonard’s conduit to the team.

Of course, the guy could play some ball, too.

Netolicky joined the Pacers ahead of the 1967-68 seasons and immediately became central to the team’s success. Over his first five seasons, he averaged 18 points and 10 rebounds per game, was named an All-Star four times, and helped the Pacers to ABA titles in 1970 and 1972. Like Brown and Daniels, Netolicky was: a) selected to the ABA’s All-Time Team, and b) made his first basketball card appearance in the 1971 Topps set.

Netolicky’s rookie card – admittedly, not the most aesthetically pleasing – can be had for a very modest sum, with PSA 8s (pop: 87) and PSA 9s (pop: 34) both available for less (often far less) than $80. Given the resume – on and off the floor – that’s worth a look.

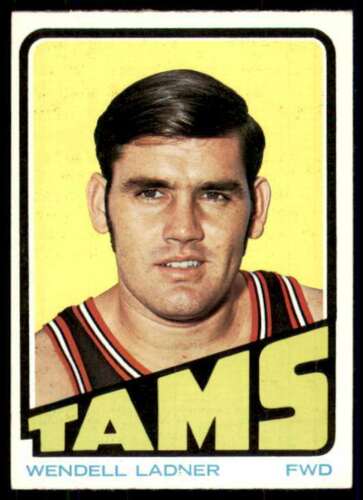

Wendell Ladner (Tams / Kentucky Colonels) – 1972 Topps #226

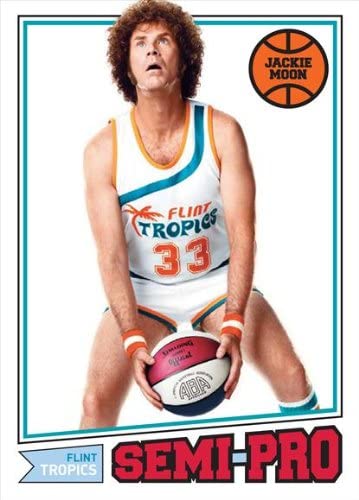

What do John Brisker and Will Farrell have in common?

What the 6-foot-5, 220-pound Ladner lacked in talent (a fair bit), he made up for in grit. In fairness, Ladner wasn’t totally devoid of ability, averaging a double-double in each of his first two seasons (a combined 15.5 points and 10.7 rebounds), and earning All-Star honors each season. Over the course of his career, Ladner averaged 11.6 points and 8.3 rebounds per game.

However, where the undrafted Mississippian carved out a niche was as an “enforcer.” Most notably, Ladner was John Brisker’s preferred dance partner, with the two regularly engaging bloody battles on the court, and then hitting the bars together post-game.

Interestingly, in a league in which “itinerant” was the norm, Ladner was a true nomad, suiting up for five teams in five seasons. After a season-plus with the Memphis Pros, Ladner was dealt to the Carolina Cougars. After a half-season, he returned to Memphis (now the Tams). After a 15-game stint in Memphis, he was sent to the Kentucky Colonels, where he provided frontcourt muscle for the remainder of the 1972-73 season and the first part of 1973-74. He was then on the move again, this time to New York, where he served as on-court bodyguard for Dr. J, and was rewarded with a championship ring.

Tragically, thirteen months after that title win, in June 1975, Ladner died in an airline crash, at just 26 years of age.

Erving remembers Ladner his wackiest teammate, saying that Ladner “wanted to be Burt Reynolds”. In fact, it’s this persona that Will Ferrell spoofed in trailers for his 1970s basketball comedy “Semi-Pro”.

Fittingly, Ladner’s modestly priced rookie card – also from 1971 Topps – is comparable in price across various grades (albeit with a smaller population) to that of… yup, John Brisker.

Louie Dampier (Kentucky Colonels) – 1971 Topps #224

A six-foot guard, Dampier is one of just six guys to play all nine ABA seasons, and one of just two to do so with one team.

Dampier played his college ball in Kentucky, where, In three varsity seasons (freshmen were ineligible to play varsity at the time) he was a two-time All-American and three-time All-SEC selection. Dampier was a member of Adolph Rupp’s 1966 team that lost the national title game to Texas Western College (now UTEP), sparking the beginning of the end of segregation in college basketball.

In 1967, Dampier was selected in both the NBA (by the Cincinnati Royals) and ABA drafts, and opted to sign a more lucrative deal with the ABA’s Kentucky Colonels. He and Darel Carrier joined forces to form one of the ABA’s great backcourts, with a frontcourt of Artis Gilmore and Dan Issel rounding out one of the league’s best teams. Three times the Colonels reached the ABA Finals, winning the title in 1974-75.

Individually, Dampier is also an ABA all-timer. He began his career with three straight seasons of 20+ points per game (peaking at 26 per game in 1969-70), and eight straight with more than 5.4 assists per game. Dampier is also one of pro basketball’s first 3-point specialists, making 500 during a three-year stretch, including a record 199 in 1968–69, and 198 in 1969–70.

Over the his ABA career, Dampier averaged 18.9 points and 5.6 assists, and was named an ABA All-Star seven times. He holds the ABA records for games played (728), minutes (27,770), points (13,726), assists (4,044) and 3-pointers made (794). Unsurprisingly, Dampier was a unanimous selection to the ABA’s All-Time Team and, in 2015, was enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

Despite his lack of NBA success (three post-merger seasons with the Spurs, averaging 6.7 points), a relatively (for this batch of cards) large population (320 graded by PSA; 167 PSA 8 or better), and the fact that no current professional fan base calls him their own, higher-grade versions of Dampier’s 1971 Topps rookie still command triple figures, with PSA 8s around $100, and PSA 9s at $400 or more.

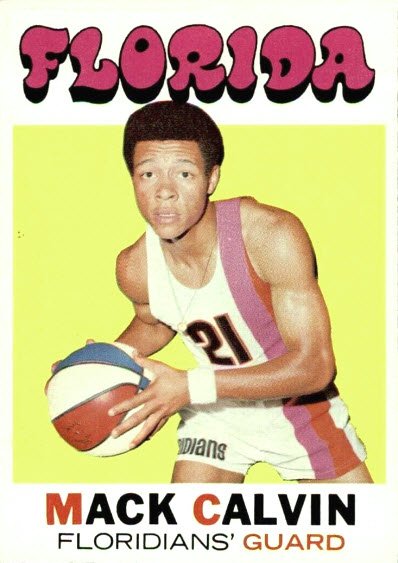

Mack Calvin (Miami Floridians +…) – 1971 Topps #195

Thanks to a rather itinerant career and a lack of team success, Mack Calvin is often forgotten in discussions of ABA greats. He is, however, one of the top scoring lead guards of his era.

Calvin spent seven seasons in the ABA, with five different teams. After an ABA All-Rookie season (1969-70) with the Los Angeles Stars, he moved on to the Miami Floridians, with whom, over two seasons, he averaged 24 points and nearly 7 assists per game, was twice selected as an All-Star and, in 1970-71, when he averaged 27.2 and 7.6 assists, First Team All-ABA. From there he was off to Carolina, where he averaged nearly 18 points per game over two All-Star, All-ABA seasons.

In 1974–1975, now with Denver Nuggets, Calvin turned in one of his best seasons, with 19.5 points and a league-leading 7.7 assists per game, which he followed up with 19.4 and six assists the following season, this time with Virginia Squires.

Calvin joined the Lakers for the 1976–77 NBA season, but, now in decline, struggled for playing time. He averaged 7.0 points per game over four NBA seasons with five teams – the Lakers, Spurs, Nuggets, Jazz, and Cavaliers – before retiring in 1981.

His place in ABA history, however, is secure, with 10,620 points placing him eighth on the league’s all-time list, 5.8 assists per game ranking third, and 3,067 assists trailing only Louie Dampier.

Based on aesthetics, rarity and the player’s body of work, here’s a strong case to be made for Calvin’s 1971 Topps rookie as the best bargain here, with PSA 8s often failing to crack $30, and, PSA 9s (of which there are 31, out of a total PSA population of 151), when available, coming in under $100.

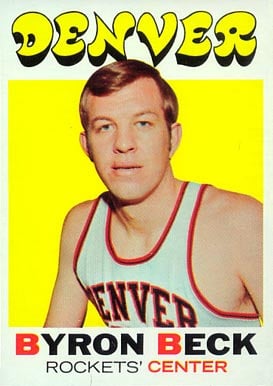

Byron Beck (Denver Rockets) – 1971 Topps #210

One of the ABA’s true stalwarts. A 6’9″ bruiser from the University of Denver, Beck spent his entire pro career in Denver, with the Rockets (later the Nuggets), taking part in more games than anyone other than Louie Dampier, and averaging a solid 12 points and 7.4 rebounds.

Like Wendell Ladner, Beck was neither particularly athletic nor overly skilled. What he was, though, was a grinder. In the three-season span between 1969 and 1971, he put up 13.6 and over ten rebounds per game, twice averaging a double-double.

The two-time All-Star is one of the aforementioned six players (along with Dampier, Netolicky, Gerald Govan, Stew Johnson, and Freddie Lewis) to play in all nine ABA seasons, and is the only player other than Dampier to do so with one team. As a result, in December 1977, Beck became the first player in Denver franchise history to have his number retired.

Given all of that, Beck’s (you guessed it) 1971 Topps rookie card is ridiculously affordable, especially in raw form. PSA 9s, of which there are 31, (admittedly, they don’t pop too often) struggling to crack $50, while PSA 8s can be had for less than a soup and a soda from the deli.